What caused the Chernobyl 1986 nuclear accident?

Foreword

The causes of the Chernobyl nuclear accident are multidisciplinary. The causes of the accident can be attributed to at least bad political decisions, design flaws, fear of authority, negligence, carelessness, technical incompetence. There is enough material related to the accident to write several books about it and many people have done so. In this blog post, I will focus only on the technical aspects of the accident. For those who want to dive deeper into the topic, I would recommend the book of Chernobyl: the history of the nuclear disaster written by a Ukrainian historian Serhi Ploh'i.

I want to make it clear that I am neither a nuclear physicist nor a historian and I am well aware that my explanation of the event may include some amount of false information. I am happy to receive any feedback on this blog post and I am willing to make corrections if it is required.

However, through my educational background, I understand the fundamentals of the physics related to the accident and have spent a few dozen hours researching the subject to understand it as well as possible. I therefore hope to be able to simplify the techical causes of the accident for those who find the topic difficult to understand.

What technically caused the nuclear accident in Chernobyl

It is impossible to understand what happened in Chernobyl without understanding, at least on a superficial level, how nuclear reactors work, so let's start with that.

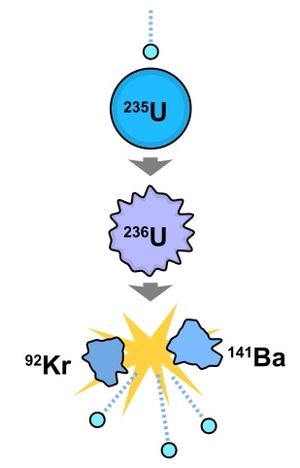

The operation of a nuclear reactor is based on a self-sustaining reaction where heavy uranium or plutonium atoms collided with neutrons. This split the heavy atoms into lighter ones and energy is released. This is called nuclear fission.

Image source: Public Domain / Creative Commons

When the atoms split apart, they also release 2 or 3 high energy neutrons which bounce around in the reactor. Some of the neutrons collide with other heavy atoms and make them split apart too. To keep the amount of colliding neutrons in control, the reaction is balanced so that only one of the neutrons released in each fission reaction collides with another heavy atom.

If more than one neutron, on average, is able to collide, the rate of the eaction increases. Correspondingly, the rate of the reaction decreases if the number of colliding neutrons is reduced.

Since every fission reaction releases more than one neutron, there has to be a way to get rid of the extra neutrons.

Three different things can happen to neutrons inside a reactor:

- They can collide with a heavy and unstable atom and cause a new fission reaction,

- they may completely escape the reactor, or

- they can be absorbed by lighter atoms that are not unstable enough for the fission reaction

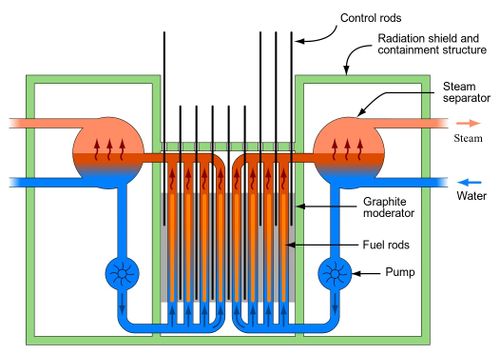

To reduce the rate of the reaction, there are materials in the that are naturally effective neutron absorbers. Examples of such materials include boron and cadmium. Absorbents are generally used in control rods that can be moved in and out of a reactor so that the reaction rate of the core can be controlled dynamically.

The fuel used in the Chernobyl was uranium. In nature, uranium appears in two forms. Uranium-238 is the more common form and doesn't normally split apart when neutrons collide with it and instead absorbs neutrons. Uranium-235 is a lot more rare and it is the fissile type of uranium meaning that it can split apart and release energy. Only about 0,7 % of natural uranium is fissile.

Uranium used in nuclear weapons, for example, must be enriched so that a much larger proportion of the uranium is fissile uranium-235. For example, in the world's first nuclear bomb, uranium was enriched so that about 80 % of the uranium it contained was the fissile type.

Due to complex quantum physical reasons, neutrons decay uranium-235 about 1000 times more likely when they move slowly compared to fast-moving neutrons. However, the neutrons released in the fission reaction move very fast, almost at the speed of light, so reactors must be designed so that they can slow the neutrons down before they collide with uranium.

The speed of neutrons can be slowed down by adding moderators into the reactor. Moderators are non fissile materials that neutrons collide with without being absorbed by them either. The most common moderators used in nuclear reactors are water and graphite. Moderators allow more fission rections to occur without a large portion of the fuel being the fissile type. This is essential because enriching uranium is very difficult and expensive.

The reactors used in Chernobyl were called RBMK (ven. РБМК; реактор большой мощности канальный; reaktor bolshoy moshchnosti kanalnyy, "high energy channel type reactor") reactors.

The channels refer to series of pipes that go vertically through the core of the reactor. The channels move cooling water and contain different amounts of fuel and control rods as well as neutron sources depending on the implementation of the specific reactor.

Image source: Fireice~commonswiki, Sakurambo & Emoscopes. CC BY-SA 3.0

While many water cooled reactors also use water as a moderator, the RBMK reactors were moderated with graphite blocks placed around the channels. This was a design choice which allowed the reaction to be sustained even when completely unenriched natural uranium was used and made the reactors very cost effective.

Electrical pumps were used to move the cooling water. The pressurised water entered the core from the bottom, heated up inside it and left it from the top. Some of the heated water turned to steam which was used to spin a turbine that generated electricity.

This brings us to the day of the accident. In an emergency, the reactor can be shut down, but the transport of cooling water through the reactor cannot be shut down very quickly. The uranium atoms that have already split leave behing fission products that are also radioactive and will keep splitting and producing heat. The cooling pumps must therefore continue to operate even in the event of an emergency. For this purpose, the power plant was fitted with diesel generators which could be started without electricity.

The issue was that it took approximately 60 seconds for these diesel generators to get up to speed, so a different energy source was needed for that period. Although the turbines began to slow down as soon as steam production ceased, due to their large size they still had a huge amount of kinetic energy and it would take a long time for them to shut down. According to the reactor design, that kinetic energy could be used to run the cooling pumps until the diesel generators start up. This had been tried three times in the Soviet Union without success, and the Chernobyl test was finally supposed to show that the security feature really would work.

On the day of the accident, reactor number 4 of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant was scheduled to be shut down for maintenance, so it made sense to schedule the test to be performed at the same time. On the day of the test, more electricity was needed for the grid than expected, so the reactor was kept running at reduced but relatively high power for many hours after the originally planned shutdown time.

At this point, it is essential to remember that controlling the number of colliding neutrons in the reactor is very important and that control rods containing neutron absorbing agents were used to achieve this. One inportant by-product of uranium fission is xenon-135 which is also the most efficient neutron absorber we know of. However, xenon does not appear as soon as uranium decays. About 95% of it only appears several hours later when another unstable decomposition product of uranium, iodine-135, decays.

During normal operation of the reactor, xenon only appears after about six hours of operation. When the reactor is running at normal power, the amount of xenon increases until it reaches an equilibrium point where equal amounts of xenon is produced and burnt in the reactor. This is normal, and as the amount of xenon increases, the reaction rate can be maintained by reducing the number of control rods.

It is essential to understand that as the power of the reactor decreases, the amount of xenon burning out decreases immediately, but its production will remain the same for the next six hours or so. Thus, reducing the reactor power causes an increase in the amount of xenon in the core, which in turn that slows down the reaction rate.

The Chernobyl reactor 4 was designed to produce energy at a power level of approximately 3200 megawatts but it was held at a level of about 1600 megawatts for most of the day. At the beginning of the test, the power was supposed to be dropped to about 700 megawatts.

When the power drop from 1600 megawatts to 700 megawatts began, the reactor's power suddenly dropped much lower than expected, to about 30 megawatts, which was far too little to run the test. At that power, the the turbines wouldn't have nearly enough energy to run the generators for 60 seconds.

At this point, the reactor was in a state from which it would be extremely difficult to bring its power back to a normal level. Xenon was still being produced and hardly any of it was being burned. This state of the reactor is called a xenon pit. Normally, to get out of a xenon pit, a reactor is completely shut down for a few day until the xenon has naturally decayed into materials that no longer absorb neutrons.

Xenon was not the only factor slowing down the reaction. The water used to remove heat from the reaction also absorbs a small amount of neutrons. At normal power, the heat released by the reaction causes some of the water to boil, creating steam bubbles that absorb barely any neutrons.

The reactor was now in a state where its core was filled with neutron-absorbing xenon and liquid water. The power plant operators decided to try to increase the power of the reactor by removing more and more control rods from the core. In order to use the control rods both to slow down and speed up the reaction, their shafts were made of neutron-absorbing boron and their tips were made of graphite, which slows down the neutrons, increasing the reactivity.

Normally, the reactor has more than 200 control rods, but to increase the efficiency of the reaction, the operators removed almost every one of them. This may sound insane, but the operators removed the control rods knowing that, if the reaction ever got out of hand, they would always be able to press the scram button, an emergency stop button which would push all the control rods into the reactor as quickly as possible.

By removing the control rods, the operators were able to increase the reactor power to about 200 megawatts, which was well below the power according to the test protocol. However, by manually adjusting the power of the cooling pumps, they were able to produce enough steam to run the turbines at the required speed.

The test began and the speed of the turbines started to slow down. When the control rods are pulled out, the water liquid water in the reactor has a significant effect on the absorption of neutrons and, consequently, on the reactivity of the core. When even a small amount of water boils, the reactivity of the reaction increases. The more the reactivity increases, the more water starts to boil, i.e. there is a positive feedback loop also known as positive void coefficient. As the power of the reactor increased at a tremendous rate, the operators decided to press the emergency stop button, at which point the control rods began to descend into the reactor.

When pulled out, the control rods settle into the reactor so that there is a little more than a meter (~ 3 ft) of space under their graphite tips. That space is filled with cooling water. When the emergency stop button was pressed, there was liquid water in the bottom of the reactor, which reduced the power of the lower part of the reactor. As the control rods descended, the water that slowed down the reaction was removed and replaced with graphite, which increased the reactivity of the reaction.

Under normal circumstances, the power increasing effect of the graphite tips is not significant, but since the reactor was in a very unstable state, the effect was enough to increase the reactor power in a few seconds to about 10-100 times the reactor's normal power. In the blink of an eye, all the water inside the reactor turned into steam and the pressure blew off the lid of the reactor dispersing the radioactive material into the air and the surrounding area.